Highlights

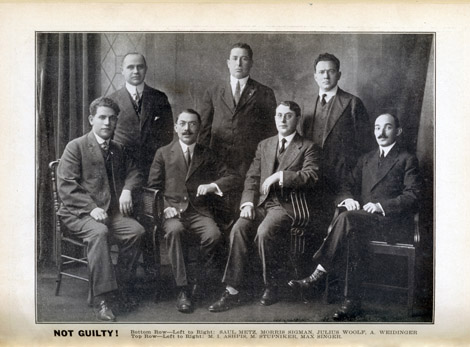

Not Guilty!

The Trial of the Seven Cloakmakers

The Great Revolt

Low wages, long hours, and late nights and weekends sewing bundles at home—horrid conditions in the garment industry that laid the foundation for unrest among the workers and desire for a general strike. Following the momentum from the 1909 strike of women shirtwaist makers, the cloak makers began planning, and at the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) convention in June 1910, a resolution in favor of a general strike in the cloak and suit industry in New York was overwhelmingly approved. The General Executive Board of the union made extensive preparations, creating a general strike committee, renting halls for the strikers, employing lawyers, and reviewing finances. A packed to capacity mass meeting was called on June 28, 1910 at Madison Square Garden and at the beginning of July, a secret vote of members resulted in 18,771 for and only 615 against a strike. The general strike began on July 7, 1910 and workers stopped, left their jobs and began filling the streets and halls. At its height, some 40,000 men and 10,000 women were involved. The strikers met in halls that were monitored by a hall-chairman, and every shop elected a shop-chairman. Roll call was taken in the halls twice a day to make sure all workers were present, and only strikers and union members were permitted inside and forbidden to loiter outside to avoid confrontations with non-strikers and spies. While each shop provided its own pickets, the General Picket Committee would provide assistance and extra people. As Chairman, Morris Sigman was responsible to see that all the striking shops were being picketed and that strikebreakers were not taking the place of the workers. Strike benefits were only available to married workers in urgent need. Many workers were desperate and not everyone belonged to the union. These men became strikebreakers by working in struck shops whose employers were eager to bring in labor. The union would locate the scab workers and bring them to the Picket Committee, where Sigman’s job included questioning the men to discover who was employing scabs, learn how many men were working in the shop, request that any money earned go to the union and strike fund, and of course get the men to join the ILGWU.

The Crime

On July 31, 1910, just after midnight, Morris Feuerwerker called out for police. As he was leaving the Picket Committee headquarters in Casino Hall at 85 East 4th Street, he was struck from behind. The police started chase and caught an individual running from the scene, Max Breiman, but Feuerwerker could not identify him as the assailant. Another man was found lying face down in the middle of the street and helped to a nearby drugstore before being taken to the hospital. Herman Liebowitz, a tailor, had been struck in the face and head suffering a fractured skull and later died from his injuries. No one was arrested for the crime and at the inquest, Feuerwerker testified that both he and Liebowitz had been at the Picket Committee that evening and while leaving after midnight, were assaulted from behind. Breiman testified that on his way home, he approached a large crowd that had assembled. He felt someone punching him, and turning around he struck back before fleeing only to be collared by the police. Liebowitz’s death was unsolved and the police began to investigate. Detectives surmised that the assaults on both men were linked and that the assailant must have been one of the strikers, many of whom were interviewed. No new evidence came to light and questions remained whether Liebowitz was maliciously pushed or accidently fell. The strike continued and when it was settled, the Picket Committee vacated the building and the crime temporarily forgotten.

Three years later, the file on Liebowitz’s death languished in the police archives. While in jail awaiting trial, “Dopey” Benny Fein, a gangster and labor racketeer, attempted to make a deal with the district attorney by confessing to other crimes. Dopey Benny confessed to the murder of Liebowitz, though he was in no way directly involved. Dopey Benny admitted to having been hired by unions to beat up strikebreakers and force shops to unionize during strikes. His confessions and alleged misdeeds on behalf of unions cast suspicion on organized labor. The case was assigned to the new Assistant District Attorney Lucien Breckinridge, who was eager for a noteworthy trial.

The Conspiracy

Max Sulkes was a private detective who ran the Empire Detective Agency. Looking to expand his business, Sulkes began providing companies that had striking employees with a new supply of workers as well as protection, in the form of large guards, for the scabs entering the factories. Essentially, Sulkes was running a strikebreaking operation under the guise of a legitimate employment agency. He placed ads in the paper looking for cloak operators, cutters, pressers and finishers, and then the workers would be deployed to shops on strike. As the ILGWU doubled the number of strikers on the picket line, Sulkes and his agency multiplied the number of strikebreakers, security, and intimidation tactics. To improve the quality and competency of his strikebreaker force, Sulkes devised to set up a social club to attract unemployed or disgruntled garment workers unhappy with the ILGWU, and in November 1913 “The International Ladies’ Garment Workers of the World, Inc.” an early racketeering labor union, was born. As strikes were called by the real ILGWU, Sulkes and his garment workers would show up to supply a scab workforce and attempt to break the strike. Taking legal action, the ILGWU, led by its counsel Morris Hillquit, filed an injunction to prevent Sulkes from using the name International Ladies’ Garment Workers, and Sulkes was forced to rename his organization the “United Cloak & Skirt Makers Union.” With a long held grudge and hostile feelings towards the ILGWU, Sulkes became interested in the Liebowitz case that his acquaintance ADA Breckinridge had been appointed, conveniently supplying the prosecution with witnesses for a crime committed four years ago.

The Trial

On the night of April 4, 1914, the police pounded on the door of Morris Sigman and arrested him for the murder of Herman Liebowitz. Two days later Morris Stupnicker was arrested, followed on April 18 by Saul Metz, second vice-president of the International and president of the United Hebrew Trades, all members of the union and all held without bail. The arrests of officers in the ILGWU and the alleged connection between the murder and the strike created a sensational story for the newspapers. Witnesses who had appeared before the Grand Jury included the doctor who performed the autopsy, the police officer at the scene, and three other men who had been cloak makers during the strike, but were now aligned with Sulkes and his agency. After reviewing the minutes of the Grand Jury testimony, the attorneys for the union, led by Hillquit, were able to get the defendants released on bail--$15,000 for Sigman, and $10,000 each for Metz and Stupnicker. Freed just before the ILGWU convention, the men were warmly received by their fellow union members and Sigman was elected the new secretary-treasurer. While the impending case was set to go to trial in October of 1914, the District Attorney’s office continued to ask for adjournments, and the trial continually postponed month after month until the new District Attorney, Charles A. Perkins, took over the case. On May 11, 1915, Sigman, Metz and Stupnicker, along with Julius Woolf, Abraham Weidinger, Max Singer, Isidore Ashpitz and Louis Holzer were arrested and charged with the murder of Herman Liebowitz and placed in jail without bail. On August 7, 1915, bail was set at a total of $135,000 for the release of all the men. The murder trial was moved to the New York Supreme Court and a date for the trial was set—September 20, 1915. The charges against Louis Holzer were dismissed on September 13 and on September 19 the seven men returned to jail to await their trial and fate.

On September 23, 1915 at 10 am in New York Supreme Court, the case of the People of the State of New York vs. Morris Stupnicker, Max Sigman, Julius Woolf, Saul Metz, Isidore Ashpitz, Abraham Weidinger and Max Singer charged in murder in the first degree officially began in what would come to be known as the “Trial of the Seven Cloakmakers.”

The Case

The main focus for the prosecution was the explanation of how Feuerwerker and Liebowitz came to be at the Picket Committee that evening. Both men had just arrived that day from Hunter, New York, where a shop had opened and was employing scabs to work. While Liebowitz had ceased work at the announcement of the strike, with five children and another on the way, he started to look for employment. The ILGWU had learned of the shop and sent some of their own men, including Max Singer, under the guise of scabs to find out the location of the shop and bring the workers back to the city. On Saturday, July 30, 1910, the union men arrived at the factory to halt production and induce the other workers to accompany them back to apologize for ignoring the strike. A scuffle ensued with the landlord of the shop who ordered the men off the grounds and the union committee was attacked and placed in jail. All returned, including Feuerwerker and Liebowitz, on Sunday, July 31, where they were brought for questioning before Sigman and the Picket Committee. After apologizing for strikebreaking and donating money earned to the strike fund, the men were released.

It is at that point that accounts on what happened next that night differ. The prosecutor’s eye-witness testified to being on the street in front of the hall after midnight and seeing Sigman, Stupnicker and the others strike Liebowitz on the head and while he lay on the ground stomp him before fleeing. Upon cross examination it was discovered that the witness, Isaac Levine, was a member and president of the Sulkes “union.” Further casting doubt upon whether his testimony was valid, there was skepticism that he was actually present the night of Liebowitz’s murder and his story most likely fabricated. A second witness for the prosecution provided damning testimony against the defendants but again upon cross examination, uncovered that the witness was pressed by Sulkes himself to concoct and tell his story to the District Attorney’s office.

In the case, the District Attorney attempted to prove a conspiracy. DA Perkins argued that the defendants conspired to stop work in Hunter and bring the workers back to the city, and therefore conspired to commit murder or assault. Since all men were members of the Picket Committee, all were guilty of the same crime. After the prosecution rested, the defense asked for a motion to dismiss the charges, which was denied and the case proceeded. Under direct examination, the defendants gave their testimony to illustrate their character, establish their whereabouts that night, and demonstrate their innocence. It was soon learned that some of the men were not even present at the hall the night of the murder. All of their statements held up through cross examination, continuing to erode the prosecution’s case. After the defense rested, again a motion was called to dismiss the charges and this time those against Metz and Woolf were dismissed due to insufficient evidence. At the end of the closing statements, the jury deliberated for only two hours before coming back with a verdict.

The Verdict

On October 8, 1915, the men were found not guilty and acquitted of the false charges. Hillquit and the defense provided the jury with detailed accounts and information on the history of the strike and the role that the Picket Committee and Sigman played in delivering relief to the strikers, preventing strikebreaking, and the eventual victory of the strike. The prosecution relied on evidence supplied by shady characters linked to a man with a known hatred for the union. There had long been a prejudice and suspicion of organized labor which enabled a case with little credible and factual evidence to make it to trial. The ordeal took its toll on all those involved, and Sigman resigned from his position within the union shortly after the verdict. Yet, even in the adverse and antagonistic situation, the seven cloakmakers prevailed and proved their innocence.

Selected Bibliography

The Elias Lieberman Manuscripts

6036/001

The collection contains the unpublished manuscripts of Elias Lieberman, including “A Portrait of a Leader: A True Labor Story of a Man and an Era,” which focuses on the life and career of Morris Sigman. The manuscript provides a detailed and eyewitness account of trial, containing opening statements, testimony, and closing arguments, as well as background information on the strike and circumstances surrounding the crime.

The Morris Sigman Trial and Criminal Case

6036/011

The complete transcript of minutes of “The People of the State of New York against Morris Stupnicker, Morris Sigman, Julius Woolf, Solomon Metz, John Auspitz, John Wedinger, and Max Singer” of the trial that began on September 23, 1915 and the minutes from the March 15, 1915 Grand Jury testimony.

"The Ladies' Garment Worker"

5780/070

“The Ladies’ Garment Worker” provided coverage on the trial, especially the months of October and November. The publication recaps the case as well as includes profiles on the accused union members.

Written and compiled by Kathryn Dowgiewicz